Review

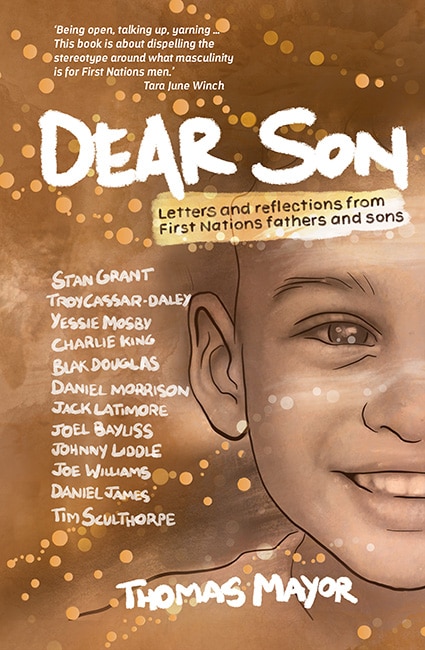

Dear Son:

Letters and Reflections from

First Nations Fathers and Sons

Thomas Mayor (ed)

Review by TYREE BARNETTE

Hardie Grant, $34.95 hb, 200 pp.

Parenting is a deconstructive process. It strips away the non-essential parts of you as you work to build a better human being with your child. In raising my two young sons, I constantly dismember and reassemble my own matter. Through this chaos of inner and outer scrutiny comes the essential elements: the purest building blocks I have to make a better version of me.

Being born in Black skin also means deconstructing how you are viewed by Whiteness, the by-product of colonialism and White supremacy. When you are born Bla(c)k, Whiteness already defines you and your offspring as negative. Much of the external world will reinforce this message.

Thomas Mayor’s collection of letters from First Nations fathers and sons, entitled Dear Son, reflects on the challenges of being a Bla(c)k father under the gaze of White Australia.

In between some of the letters are poetry depicting Indigenous life and culture. Mayor’s book is a direct response to late Australian editorial artist Bill Leak’s racist cartoon printed in The Australian.

In the drawing, Leak depicts Indigenous fathers as irresponsible alcoholics. A police officer presents an Indigenous boy to his father, instructing him to talk to the boy about personal responsibility. The father, holding a beer can, asks the officer for the boy’s name, seeming to not recognise his own son. This divisive image is how some Australians view Indigenous fathers.

As further insult, The Australian stood by the image following backlash. Supporters of the cartoon claimed that Aboriginal communities neglected their children as evidenced by high youth incarceration rates and other social inequalities. This common tactic by Whiteness of victim-blaming is especially disempowering as it removes the context of how the oppressed came to be so.

Dear Son restores truth and offers counter images to Leak’s cartoon by humanising Indigenous fathers. The collection of letters present vulnerable men, hurting men, gay men, grieving men, divorced men. It gives a three-dimensional picture of Indigenous men grappling with the complexities of life in the modern age that counters Leak’s condescending view.

Dear Son is a destructive force. Each first-person reflection, written with incredible vulnerability, disassembles negative portrayals. Mayor strikes the first blow with an apology, a history lesson, and reflections on how to build a better manhood. Stan Grant speaks about his father’s efforts to preserve and pass on language, connection to land, culture, and practices. Troy Cassar-Daley expresses the pride that he already sees in his son Clay, and the importance of breaking intergenerational cycles of economic dependency and broken homes.

Yessie Mosby tells his sons about his expectations of them, their cultural practices on Zenadth Kes (Torres Straits), and collaborating with the Western world to fight climate change. Charlie King writes to his deceased White father celebrating his legendary accomplishments and discusses his admiration for the love he had for his Aboriginal family. Blak Douglas also writes to his father in admiration for his relentless work ethic, fight against racism, and the importance of affectionate love.

Daniel Morrison admires his son’s acceptance of Morrison’s homosexuality, and the importance of being true to oneself. Jack Latimore speaks of a trip he took with his father to visit a dying relative and reminisces on a number of family stories he’d recorded to pass to his children. Joel Bayliss talks to his son Isaiah about the sustained oppression of White Australia against Aboriginal bodies, how he fights back, and instils that same fight in his children.

Johnny Liddle explains to his sons and grandson the importance of respecting the struggles of their elders. Joe Williams details his battles with substance abuse and mental health during his professional sporting career, and how connection to country and culture helps save him. Daniel James speaks to his father about his memories of him growing up as a fiercely proud Aboriginal man. Tim Sculthorpe weaves stories of his Tasmanian Aboriginal heritage and his business that focussed to preserve it. Mayor ends the rebuttal of Bill Leak’s cartoon by thanking his own father for ‘… preparing me for a world that would not love me like you do.’

I am reminded of a quote attributed to Steve Jobs says that ‘being a parent is allowing your heart to walk around outside your body’. Being the parent of a Bla(c)k son is allowing that exposed heart into a world that seeks to dismantle it.

I have two hearts currently outside of my body. Through my African-American Australian boys, I get to observe the world anew – without preconceptions of what essential elements should or should not constitute a Black boy.

And while I cannot speak towards the unique experience of being Indigenous, especially in Australia, I understand and relate to the experience of being both a Black father to Black boys, and the son of a Black father. This book also empowers me, and all Bla(c)k men, who experienced the dismembering of their own positive image involuntarily to fit the narrative of Whiteness, White supremacy, and colonialism.

My oldest son Hampton is tall, lean, beautiful, and gentle. He wants to be liked – like me. I love his desire to connect with others. I also fear a world that won’t always accept his hand. Hampton is very inquisitive, highly perceptive, and ‘cheeky’.

My second son Miles takes after his mother: headstrong, assertive, and advanced for his age. Miles will play with others but seems not to suffer their approval. I fear his strong sense of being might be perceived as threatening or anti-social to Whiteness.

I often daydream about my sons as adults, video calling me from various corners of the globe. We’ll talk about dating, how their careers are going, and I’ll end the call by bestowing some great piece of wisdom. I wish to always be their safe harbour in a turbulent world.

In the first letter by Thomas Mayor, he discusses a strained relationship with his father while growing up. Mayor acknowledges his father carried hidden scars from racism and mistreatment as a boy raised in the Torres Strait Islands. Through his father’s example, Mayor breaks the curse of stoic masculinity where emotional pain and trauma are buried and untreated. He encourages his son to, ‘… believe that a person’s depression is real, and like other health afflictions, requires care’.

In examining his own masculinity, Mayor expresses regret to his son for making homophobic and sexist comments to him while he was younger. Mayor also disassembles the patriarchy that helped end his first marriage through his uncompromising gender roles. His son is made better for these lessons. When he moves out on his own, he can cook, clean, and is encouraged to express his feelings.

Mayor goes on to discuss the ‘warm love’ his father shows his grandchildren. It made him reminisce about how close Mayor and his father were when he was a boy. ‘Why can’t he love me like he once did?’ Mayor asks himself in his first letter.

Hard love is something that Black American parents often give to their children. We are raising armoured young people who can withstand the Bill Leak cartoons, news articles, mug shots, incarceration rates, the police, and other mechanisms of Whiteness. Everyone of them will scream out messages of inferiority and exclusion.

In Ta-Nehisi Coates’ book, Between the World and Me, which was a letter to his young son, he talks vividly about his discovery of new ways of love. It came from a bisexual woman he liked in college who was involved with a married couple – also bisexual. Coates recalls how the woman drove him home and took care of him for hours when he suffered a migraine.

As a contrast, Coates remembers his grandparents’ authoritative approach with the rod. He explains that violence was a tool in raising Black children in America: either I can beat you here or the police will beat you out there. Life lessons came hand in hand with assaults on the body. Coates said, ‘I grew up in a house drawn between love and fear. There was no room for softness.’

While Mayor enjoys warmth from his father as a youth, he later endures being called stupid and his father’s cold promise to never read anything he wrote. Coates identifies the motivating factor of the rod as fear. For Mayor, he explores his father’s upbringing in Queensland: a state so steeped in racism that it inspired apartheid in South Africa. Mayor gives a history lesson starting from 1901 with the White Australia policy, slavery of Indigenous people, stripping of language and culture, and genocide written into legislation. This oppressive history squatted on the shoulders of Mayor’s father and drove the fear of raising a Bla(c)k boy in Australia into him. Dear Son touches on the psychology of Bla(c)k fatherhood, offering both an explanation and apology of the approaches of past generations. It also offers a blueprint on how to construct the matter of better men.

Evolving masculinity is a common theme in the book with another example in Daniel Morrison’s letter. He discusses his son’s immediate acceptance of Morrison’s homosexuality. Masculinity and fatherhood are often only portrayed from a heterosexual lens, so this entry is a positive inclusion.

Morrison tells his son ‘… that the most important thing is to be true to yourself’. Morrison did not come out publicly until his mid-thirties and reveals that he suffered from depression and anxiety for years. In contrast, Morrison admires how comfortable and confident his son and daughter are with being proud of their Aboriginal heritage, their athletic ability and passion for sport, and their resilience. He cautions that they will need it to survive in a world that limits them because they are Indigenous. Morrison’s message to his son is another lesson borne within the reconstructive exercise of fatherhood.

Morrison’s message about being true to oneself is powerful for me. My two African-American boys are growing up outside of America. When they are older, they’ll encounter Black American culture propagated by non-African Americans here. Someone will introduce music, food, clothing, dance, image, or slang and will instruct them, ‘This is who you are.’

My role is to dismantle these messages by equipping my sons with a strong knowledge of self. I will tell them, ‘You are not a stereotype or someone’s experiment of having a “Black encounter”. When it comes to your identity, cater to no one.’

They will need this mantra to counter the experience from Daniel James’ passage in his letter: ‘My life was made hard by pumpkin-headed kids who were fed lies by their parents…’

It’s also a point echoed by Coates in Between The World and Me where he says to his son, ‘… my wish for you is that you feel no need to constrict yourself to make other people comfortable.’ Bla(c)k fathers in the West and in Australia must encourage their kids to actively repel the images of Bill Leak, the reflections that Whiteness shows them of Bla(c)kness – and be proud of themselves.

James’ entry towards the end of the book is a love letter to his father. He speaks about his father’s private pain of losing a loved one and grieving alone. James again highlights the need to recognise mental illness in Indigenous men that Mayor did in his letter. Aside from grieving alone, Indigenous men often endure other periods of solitude throughout their lives: working in other towns to support young families, working on the road, fighting wars on foreign lands, or kids growing up and moving away from Country.

Dear Son highlights something important here: while Bla(c)k fathers must fortify their sons against the White gaze, there is also a need for healing among generations. James identifies in his first passage the historical effects of trauma that visit children from their parents. These intergenerational curses are hard forces to break. A good start to dismantling them is recognition and appreciation for the wounds carried by our elders.

Stan Grant further humanises Indigenous men by recalling what he did during his father’s last days inside Sydney’s Royal Prince Alfred Hospital. Grant could not visit his father in the intensive care ward due to COVID restrictions, so he drove by the hospital each night yelling in Wiradjuri language, ‘Bumaldhaany Babin’. He wants to remind his father that he is a warrior. Like other Indigenous elders, Grant says that his father, ‘… is scarred from Australia’ due to years of hard labour for little pay and oppression. Grant touches on his father’s sadness, how you could glimpse all the long years on his face. He was a warrior, but not impervious to pain.

Grant’s father also saves Wiradjuri language, writing it down in a dictionary, so that a new generation of Indigenous youth could speak it. Grant ends on the fear of losing his father, the inevitable grief we all face with the loss of a parent. When he speaks the whispered memories that you eventually cling to when loved ones pass away, I remember two elders in my family. I lost my great-grandmother and my grandfather within three years of moving to Australia. The memory of them dulls over time. I cling to what their voice sounded like, their smell, the sound of their footsteps, my great-grandmother’s adorable smile, and the softness of her cheeks on my lips. I will likely live another few decades with these dissipating memories.

Daniel James brings up an unexpectedly common thread between the Indigenous Australian and African-American experience when he discusses his father fighting in the Vietnam War. His father’s platoon commanding officer was likely a racist. African-American soldiers endured similar experiences under racist leadership. Black American men risked their lives for a war foreign to their cause and fought on foreign land. Those that made it back home endured further racism, mental illness, and acrimony from an American public that didn’t support the war.

James also discusses the lack of traditional Indigenous knowledge his father had. ‘What chance did you have to learn about the traditional way of life, when those who could have told you were wiped out at least three generations before you were born?’ By the time local leaders erected plaques and memorials recognising traditional owners of those lands, James’ father had moved on.

While my roots lie in the American South as a product of the transatlantic slave trade, I cannot trace my lineage back more than four generations. West Africa, my ancestral home, is foreign to me. Similar to James’ father, the ties I had with any tribes, nations, or customs that my ancestors practiced were severed long before my arrival.

With the Indigenous Australian experience, Dear Son describes the matter of what makes a man in a more thoughtful and inclusive form of masculinity. The book details threads of grief and loneliness that Indigenous men feel along with how they attempt to mask their pain for the sake of traditional masculinity. It discusses the humanity and insecurity within the identity of Aboriginal men, including those in the gay community. The collection underlines the need for embrace, the warm love – hugs and cuddles rather than fear and violence towards young boys.

By the final page, the Leak cartoon is rendered mute, a clumsy mechanism of Whiteness that is constructed of toxins. Mayor’s work moulds together the deconstructive process of parenting for Bla(c)k fathers in colonised spaces. His book guides all of Bla(c)k humanity on how to build the next generation better while healing our lineage of old wounds.

Tyree Barnette is a member of the Sweatshop Literacy Movement in Western Sydney. An emerging writer, he has been published online by SBS Voices and contributed to Sweatshop anthologies this little red thing and Racism: Stories on Fear, Hate and Bigotry. Tyree is working on his debut novel thanks to a mentorship by Affirm Press and Sweatshop.