Fiction

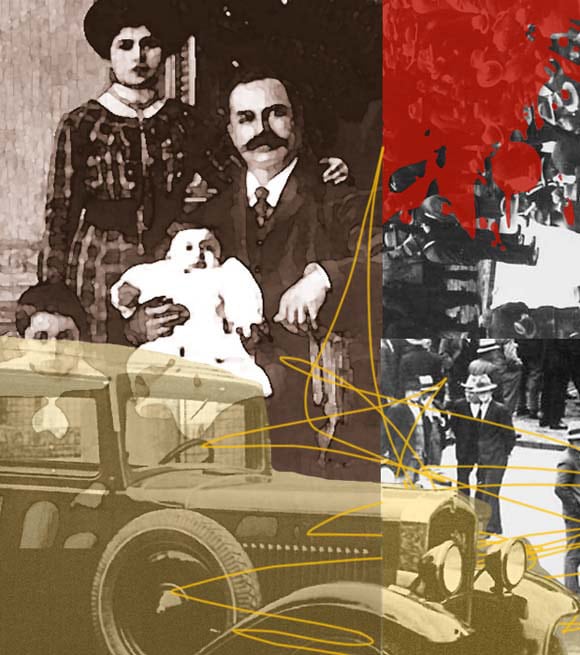

The Rally 1928

An excerpt from a novel in progress

by HARIKLIA HERISTANIDIS

Loula held her breath as Anesti helped her into the automobile. She had seen a few horseless carriages on Kastoria’s cobbled streets, black smoke trailing them like a noxious tail, but she had never imagined riding in one. She placed one foot on the running board and then the other inside the vehicle. Carefully she flattened the back of her blue cotton dress before sitting down. Parliamentary elections were a week away and today her husband was campaigning in the town of Florina. The automobile would get them there and back home in less than a day.

‘All ready, dear Loula?’ Anesti asked. ‘Steady now, I’ll pass the baby to you.’ Every time her husband called her dear Loula she thought of her papa, God rest his soul. Eighteen months had passed since he was taken from her, leaving Mama Eleni a widow a second time.

Lord, how she missed him. The scent of his tobacco wafting from a stranger’s pipe still stopped her short; and phrases like dear Loula, thrown out by her husband, hit her like a sack of flour in the stomach, where her grief had lodged, heavy and intractable. Loula hardly knew how she would have survived any of what they had been through without her father’s cheerful disposition and positive outlook. She could still hear him saying, Stop fussing, my dear Loula, even as he lay bedbound. Right up until the end she had sat at his bedside, reading aloud from The Count of Monte Cristo.

When her papa took ill, Loula wrote to Uncle Eugene in Thessaloniki. She remembered how eagerly her father had looked forward to each new chapter of Alexander Dumas’s book, when it first appeared, serialised in one of the Constantinople newspapers. Uncle Eugene immediately found a hardback copy in Thessaloniki’s famous Molho bookstore, and mailed it to her. The book was still marked, just over half way through, with a prayer card of a guardian angel following two children, at the point where Loula stopped reading when her father’s breathing became strained, the coughing debilitating and his handkerchief stained with blood.

Mitso, now a robust seven-year-old, bounded into the automobile from the opposite side and sat next to his mother, before Anesti took his seat. The driver closed the door and took his position at the wheel. He looked in the rear mirror, put the vehicle into gear and they were off.

‘Two hours will pass in no time,’ Anesti said looking at his new gold pocket watch. ‘Thanks again for bringing the children and accompanying me. I know it’s difficult with the baby, but my convictions and the policies of the party will carry more weight with my family by my side.’

Loula squeezed his hand, momentarily letting go of the strap on the side of the automobile door. Her other arm lay still, nestling baby Athena in her lap. Making Florina in two hours was a small miracle but what noisy and smelly contraptions automobiles were. She thought of the grey mule her in-laws owned, back in Kesmek, and recalled stroking its lovely soft ears. But for the life of her, she couldn’t remember the creature’s name.

‘Look, the motion of the vehicle is already sending the baby to sleep,’ Anesti said. ‘You needn’t worry. Let go of the strap, you’re perfectly safe. Dimitri is a good driver.’

‘That’s my name,’ Mitso chirped.

‘Yes it is, precious,’ Loula replied, smiling first at her son and then her husband.

She had prayed for another boy when she found herself with child again. To be named Pavlos, after her father. But the new baby, now nine months old, had been a girl, and tradition dictated she be christened in honour of her husband’s mother. Loula had hoped to persuade Anesti to name the baby after Yiayia Elisaveta. They might call her Veta, as a diminutive.

‘The next girl can be named Athena,’ she said to her husband when the idea first came to her.

‘You’ve got it the wrong way around,’ Anesti replied.

‘I know it’s not the custom, but must we always follow tradition?’

‘Tradition is key,’ her husband bellowed. ‘Without our values and beliefs, without holding close what makes us Pontian, we lose our culture and consequently lose ourselves.’

He had turned into quite the orator. It suited his political ambitions, but Loula also saw the anger he carried within him. It had not there before the Asia Minor Catastrophe, as it was known. Sometimes Loula felt she had it too. A fury and bitterness, like an infection of the soul that came from witnessing the worst of humanity.

‘I’m hot,’ Mitso said pulling at his miniature bow tie.

‘Just leave it,’ Anesti admonished.

The boy sat rigid. Loula too held her breath, until a minute later when Anesti rolled down the window on his side. Dust and a gust of warm air blew in and he quickly wound it up again, leaving only a narrow gap. ‘Is that better?’ he asked his son, touching the boy’s arm.

‘Yes, thank you, Papa.’

‘We are, as a nation, only a hundred years old.’ Anesti’s voice boomed over the small crowd that had gathered to hear him speak in Florina’s town square. He stood on a low wooden platform, behind a table that served as a podium. There was a jug and glass of water to one side, and in the centre a hand-written page of notes, though Anesti did not refer to them. Toward the back was a row of chairs. Loula sat with the baby on her lap, Mitso beside her.

‘Stop swinging your legs,’ she whispered. ‘Sit still.’

Next to the boy were two local men, members of her husband’s party. To the right of the stage the blue flag of the People’s Party hung limp in the stagnant air. On the opposite side was the flag of the Hellenic Republic, also blue but with a large white cross, representing the Orthodox faith of all Hellenes.

‘One hundred years since we threw off the Ottoman yolk,’ Anesti went on.

There was a muffled cheer. The crowd consisted mostly of men. They were a mixed group. Some wore suits and straw hats, others were in shirt sleeves and cloth caps. A well-dressed woman caught Loula’s eye. Her hat, broad as an umbrella, cast shade on her pale, puffy face.

Loula wondered how long it would be until women were given the vote. Just that year equal suffrage was procured in the United Kingdom. It had taken radical acts of civic disobedience, sacrifice and dedication, even in that more progressive society. She looked at her tiny daughter, sitting up happily in her white dress and bonnet. Surely by the time Athena was grown, things would be different for Greek women.

‘Hellenism and the Orthodox church, however, have a long history dating to before Byzantium. A glorious past,’ Anesti continued. ‘We may be a small country with little power, but shouldn’t we aim to be the best we can be? Shouldn’t we strive for the ideals set by the ancients?’

‘The government of my opponent in this prefecture is the government of Venizelos. I say, the old Cretan has had his day. Not only is he an arrogant narcissist, but his politics and methods are of a bygone era.’

A rumble of disagreement came from the audience, which her husband ignored.

‘My party, the People’s Party, is one that will work to achieve benefits for society as a whole. We are a party for all of the people: workers, peasants, tradesmen and the bourgeois class.’

‘And the king,’ someone yelled, though it was difficult to tell if they were for or against the deposed monarch.

‘Yes we hope to restore King George II to the throne, following a plebiscite—a democratic vote of the people. We believe the monarchy to be a uniting force. We believe in Hellenism. Venizelos and his Liberal Party believe in licking the boots of the English, and the other so-called great powers.’

Anesti’s voice rose. ‘Why pander to those whose nations are built on our achievements?’

He began counting off on his fingers. ‘They mimic our democracy, they mimic our philosophy, they mimic the tenets of scientific enquiry. Why, they’ve even revived the Olympic Games, a concept given birth in Greece almost three thousand years ago!’

Loula saw many in the crowd nodding in agreement. Anesti was winning them over.

He continued. ‘But when push comes to shove, their own interests come first. They acquiesce to Turkey and we are left to perish. So much for alliances.’

It was hot in the sun. Following a cheer from the crowd Anesti paused to have a drink of water. It was then a group of men from the back, began to push their way forward. Loula watched uneasily as they shoved aside those in their way.

‘Long live Venizelos!’ one of the men shouted.

‘You’re entitled to your opinion,’ Anesti said, raising his voice. ‘But this is my platform.’

‘Right-wing scum!’ the man yelled. He wore a dark grey waistcoat over a white shirt, with sleeves rolled up. On his head was a brown trilby.

Loula tensed. Sensing her unease, the baby squirmed in her lap. The man was angry, his face red as her yiayia’s beetroot salad.

‘I’ll be taking questions in a few minutes,’ Anesti said, trying to manage the changed atmosphere. ‘You may have your say then.’

‘Bootlicker!’ someone in the crowd retorted.

‘Who said that?’ the man in the brown hat shouted, spinning around.

Loula couldn’t tell if he was tripped up on purpose or if he simply lost his footing, but when the man in the brown hat dropped to the ground, his cohorts began throwing punches. Anger curled through the crowd like black smoke. There was shouting and the baby started to cry.

Loula stood up, Athena in her arms, Mitso clinging to her dress.

‘Please, there’s no need for violence,’ Anesti called. ‘We’re civilised people.’ But like gas released from a bottle of soda water, there was no going back. The local men from her husband’s party rushed forward and pulled Anesti off the podium.

All at once Loula was alone with the children on the raised platform. They were like a row of pigeons on a fence. Dust blew up from the ground, chocking the dry air as the crowd twisted this way and that. Some ran, others held firm, punching and kicking almost carelessly. The noise was alarming. Two stray dogs barked and all the while the baby screamed. These ruffians were no different from the Turks who raided Christian villages, back in Pontos. Killing men, defiling women, stealing. Were all men savages at heart?

Anesti. She had lost sight of Anesti. The wretchedness and uncertainty of their years apart pulled the breath out of her. She felt her legs weaken, as she did the day Aristotle and one of the other teachers brought Anesti home, when he was beaten and his wedding ring stolen. His face, unrecognisable, sprang to mind. Loula shut her eyes but the image remained, etched inside her lids. Blood. So much blood. His lips purple. Swollen to bursting. A patch of skin turning blue-black. Spreading across his cheek. Vivid as a nightmare.

‘Courage Loula. He is alive,’ Aristotle said. ‘It could have been worse.’

It can always be worse.

Such a dear man. A gentle soul. Like her papa. Of course good men existed, but God seemed to take them first.

‘Mitso, quickly now,’ she said, regaining her composure. Fainting would help no one. She had her children to protect. ‘Follow your father. I’m right behind you.’ She held Athena close to her chest, even as the baby wailed. When she looked up, the man in the brown trilby was suddenly before her. His face was dirty from the fall and his hat crushed.

‘Your husband is a fascist,’ he screamed.

Spittle from his over-sized lips sprayed the scorched air. Loula flinched. Her heart thumped, but she was no longer afraid. She was angry. She had not survived the blade of the Turks to kowtow to the likes of this brute.

Time stopped, as if to give her a chance to think. Calmly and without faltering or stopping to consider her words, Loula repeated her husband’s phrase, You’re entitled to your opinion, before hurrying away. Behind her the man grabbed the People’s Party flag, threw it on the ground, then struck a match, setting it alight.

One of her husband’s colleagues rushed toward Loula, eyes wide, perspiration running down his scarlet face. He took her arm and led her to the car. It stood idling, the driver at the ready, Anesti sitting at the open door with Mitso beside him.

‘Quickly, my love, he said, shuffling along. ‘Thank the Lord you’re safe.’

As the car drove away in a cloud of dust, she saw a troop of policemen arrive on foot, holding batons.

Anesti lit a cigarette and inhaled deeply, as his right leg bounced up and down with nervous energy. ‘That scuffle won’t help my chances,’ he said, exhaling.

‘Papa, why were those men angry?’ Mitso asked.

‘Idiots!’ Anesti exclaimed.

‘We’re all safe,’ Loula said rocking the baby. In all the commotion Athena’s bonnet had been lost. ‘That’s all that matters.’ She straightened the baby’s white dress, soiled by soot and grime and a smear of blood, that she could not account for.