Essay

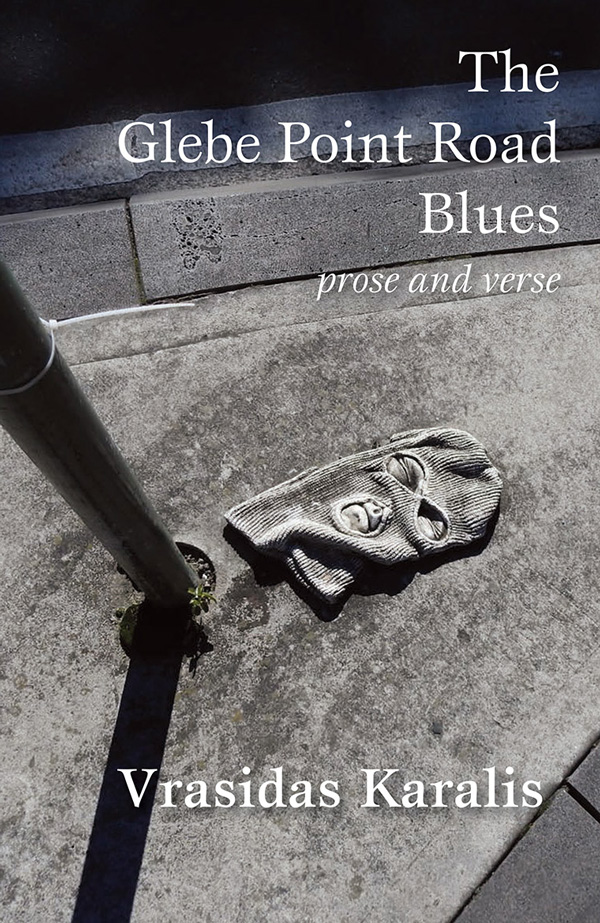

Rapture in Osmosis:

Vrasidas Karalis’ The Glebe Point Road Blues

by DAVID ROBERTS

Vrasidas Karalis’ The Glebe Point Road Blues (Brandl & Schlesinger, 2020) is a singularly haunting reading experience. A simple definition of its form might be elegy: its primary function is to pay respect to the memory of people who, though they were inhabitants of Glebe Point Road, remained profoundly homeless until death. Through its liturgical incantations, the book resurrects and redeems the deceased by providing a celestial resting place. It also reasserts these metaphysical nomads into the cultural histories from which they were tragically sundered in life.

To these ends, the book is an attempted sanctification of “the Road,” whose onrushing urban impulse toward cosmic death renders it an antipodean River Styx, a passage that affords no return, a “fatal stream.” As purgatory, it acts as a fine microcosm for Sydney, referred to as “the City” with mock-reverence in the first section of the book. (One thinks of a prefab, plywood Istanbul, whose name, as Karalis pointed out at a writers’ festival in 2012, derives from the Greek phrase ‘Is tin poli,’ meaning ‘Into the city.’)

A truer name for Sydney might be the less religiose ‘global village’, given its propensity for collapsing many cultures into a monocultural melange, a melting pot with a decidedly Anglo-Saxon skin. And of course, there is no one ‘City’ now anywhere: just a postlapsarian urban sprawl that girds the also nominal ‘Earth’.

It follows that a primary intertext is Virgil’s epic poem The Aeneid (29-19 BC), wherein the hero Aeneas is exiled from Troy and commanded by Hector to found a great city overseas, Lavinium, now Rome. The story is one of irresolvable homelessness, where the Trojans not only lose Troy to the Greeks, but Aeneas unwittingly founds a new city in the Trojans’ original, forgotten homeland. To paraphrase L.P. Hartley, the past is indeed a foreign country: one can as much reclaim a past land as one can recapture lost time. This return, this nostos, is no homecoming. What is lost is irretrievable, perhaps unrecognisable.

This is opined, both openly and not, by the deracinated denizens of Glebe Point Road. “We come here like Aeneas,” laments café owner Pascal, whose own irreconcilable estrangement from Belgium is channelled into incandescent nihilism. “We must uproot the past, our memories, our origin. There is no place to go back to. Except perhaps to die. But no, we will die here. We cannot escape.”

For Pascal, the River Styx terminates in a cul-de-sac whose black tar pitch he can only force to scintillate by dint of his white-hot rage. He is a fallen angel whose litany of sins stands between him and his ‘origin.’ In the disquieting chapter ‘And Then the Voice’, Pascal begins to confess these sins to the book’s central persona (think, perhaps, Karalis in cassocks, kalimavkion). Pascal’s opening brag – “I did beaucoup bad things. Many bad things that I do not regret” – eventually gives way to a horrifying confession – “Yes, I killed my mother… We were lovers since I was fourteen” – and ends with the mortified sobbing of both men, who are shattered by the height of the Fall.

But for all that the persona finds Pascal’s behaviour abhorrent, he is able, nonetheless, to place it within a shared European cultural continuum. “Pascal, Oedipal things end badly,” he says, which Pascal reappropriates with Freudian élan, “Precisement, c’etait comme l’Oedipus!” Startlingly, in a moment of transcendence, the men are now commiserating over their lost motherlands. The chapter ends beautifully, “They are engrossed in their anguish. They fail to notice the boy who frisks both their bags, in which they have their wallets and their most precious possessions. The photographs of their mothers on which their own damnation and graceless lives still depend.”

This conjuring of Oedipus provides succour for both men, but a direct link to home is achieved by the persona, who reaches past Pascal’s invocations of The Aeneid to endorse the perspicacity of Ancient Greece, not Rome. A similar impulse animates Karalis’ book, where the progression from prose to verse not only recalls Virgil’s painstaking drafting process, but aspires to the oral tradition of Greek poetry, under whose shadow Virgil toiled.

There is something Aeneas-like in Pascal’s oblivion to The Iliad (c. eighth century BC) as the true urtext: he appears, like that Xeroxed urchin of the Aegean, unable to recognise his origins. But there is no denying that transcendence is achieved by the Belgian and the Greek through ‘osmosis.’ Together, they are able to find a common refuge within their shared cultural heritage.

The excavation of history as a way toward redemption is a philosophy upheld, if complicated, throughout the book. The doggedness of Karalis’ archaeological dig is apparent when he blasts through the stratum of antiquity and describes, through the visions of Dean, a vagrant cryptozoologist, “a dwarf, two-legged, turkey-sized dinosaur being devoured by bigger beasts of indeterminate origin.” In ‘Cleaning Windows’, Dean is shown to be one of many liminal deities who populate Glebe Point Road: he guards the thresholds between discrete epochs, between the terrestrial and celestial realms. Propounding on his vision, he prognosticates and eulogises: “I can see them and hear their cries as they are devoured by raptors and Australovenators in the early Cretaceous just in front of the Glebe Post Office.” This is at once a prehistoric event and a projected apocalypse: beginning and end times in one.

Homelessness appears a precondition for this power to see the past, present and the future overlayed. Nowhere is this more emblematic than in Dean’s ability to divine “ectoplasms, materialised spirits” in the runic swirls he creates when cleaning windows. These spirits are angry: “They hit back. They scream,” says Dean. The windows belong to the University of Sydney. Dean continues, “This place of stone… is built on an ancient graveyard. There are many spirits lurking under its foundations. They demand to be released.”

Dean’s visions are mainly populated with the sundry predations of Australian dinosaurs, but here, through his detection of an “ancient graveyard,” he appears to channel an evisceration altogether more recent in our violent history: Indigenous genocide. Like Karalis’ persona in conversation with Pascal, Dean, also homeless, employs a continuum to chart our descent and pinpoint the locus of our Paradise Lost, our Original Sin. His contention that “…the seeds of our destruction were planted during the late Cretaceous period” enfolds time itself and conflates two epochs to expose the barbarity, the something prehuman, at the root of colonial settlement.

Mainstream Sydney, as Karalis writes in ‘Ode to the New Millennium’, is governed by “the superstitious cult of nowness.” Quite the opposite to Dean, its inhabitants exhibit an “inability to envision what follows” and a “voluntary blindness about what was here before,” resulting in a “weakness to deal with the confusion and the brutality of collective myths.” This neatly describes the blissful ignorance of those who feel at home on stolen land. Dean predicts the consequences of such ignorance: “We are doomed to be devoured by the invisible dinosaurs and the hidden animals who live side by side with us and we simply ignore them.”

With which (pre)sentiments the author concurs. In his ‘Epilogue to Style’, which closes the prose section of the book, Karalis writes about Glebe Point Road: “The place is crucial because it is specific. There is something unsettling about its actual experience which inspires to explore its imperceptible energies. In the new world societies, people live in an eternal now. They are enchanted by its presumed innocence.”

In the narrative, the location of an “ancient graveyard” under the University of Sydney is similarly crucial: it seems to transmit into the River Styx a toxic runoff of suppressed historical trauma, since, in real life, the university sits at the opening, or mouth, of Glebe Point Road.

In ‘Did He Really Exist?’ (whose very title questions the possibility of redemption), a Balkan exile is disturbed by the psychogeography at this particular junction: “As Alkis takes a taxi at the corner of Glebe Point and Parramatta Roads, he has a metaphysical moment and whispers, ‘This is the navel of our city. Our centre, our grave.’” One grave, it seems, portends another.

In ‘The Moment’, an Iraqi Jew called Menny, another exile, wanders the university campus, and as with Dean and Alkis, his terrestrial homelessness puts him in communion with the Indigenous spirits who cry for recognition and memorialisation. He addresses the quadrangle, “Oh, ecstatic voiceless building, you are a living Kaddish, a living Kaddish in stone,” which acts to envelop the dispossessed Indigenous within his own cultural prayer. The chapter ends in an ecstasy of osmosis, wherein Manny’s empathy unleashes a convergence of all times and cultures: “His voice was heard by everyone, even by the ancient tombstones at the Nicholson Museum, and by the paintings at the grand offices, and through the underground tunnels where the old sacrifices took place. And the spirits of the building wept.”

Menny’s ‘moment’ is but one stage in the great purgation or sanctification of the Road. The events of the prose section are often set in the years and months leading up to the 2000s. They anticipate an Armageddon seemingly proposed by Y2K, but when the Armageddon comes, it is unclear when it does: it was perhaps already happening and perhaps still is. It seems to derive from the “ancient graveyard” under the University of Sydney. In the last prose chapter, ‘The Fallen’, Karalis describes how the campus succumbs; there is “dense breathable blue mist,” “the shiny entrance of the Museum… covered by blood” and sounds of “crawling animals, crackling glass, human gasping…” The jacaranda in the Quad, imported tree of wisdom, collapses in what many consider an “evil omen.” “Humans got the blues. The deep blues,” Karalis writes. “They were not themselves anymore.”

Depictions of the university leading up to this moment suggest an institution that has fallen to bureaucracy, and it is fitting that an Indigenous homeless man, Pete, reminds us of the promise, since broken or lost, of the tertiary education system. “I studied arts and politics,” he says. “Blame it on Whitlam, if you know, the great white elder, free education, no money, freedom.” Nevertheless, Pete suffers the indignation of homelessness in his own homeland. After a life of struggle and privation, he suddenly disappears.

This, or death, is the fate that befalls the homeless of Glebe Point Road during their perpetual Day of Reckoning. Their very existence is perpetual reckoning: by way of their limbo, their losses, their asceticism, they attain to the ultimate truth. Befitting their elastic conception of time, their doomsday unfolds in the everlasting present, as do the events of The Book of Revelation in Eastern Orthodox belief. Thus they are saints, seraphs, psychopomps, angels: liminal in every sense.

Dean, having made his predictions, evaporates; Alkis “departs” on a “warm, beautiful day”; Menny refers to his “moments of reckoning” in the face of a cancer diagnosis. It is clear these wayfarers – Dean, Alkis, Manny, Pete – have each been assumed into Heaven. As a corollary for the real-world relocation of minorities, such as that which took place on Glebe Point Road before the Sydney 2000 Olympic Games, this celestial exodus is something extraordinary, a feat of sublimation by Karalis.

With each ascension, it appears that damnation looms larger on Glebe Point Road. When a victim of the Stolen Generation disappears in ‘Carol the Pianist’, Karalis writes, “Glebe Point Road is empty without her. The road itself feels empty without her.” In ‘Elegy to a Poet’, a proponent of “Heidegger… the principle thinker of homelessness,” ultimately “kills himself because he feels that something ominous and wordless and unpoetic is happening under his nose and that he, unconsciously, is part of it.” Only Oby, whose occult sect shows an unsettling affinity for British colonialism, raises the question of ascension or descent.

Australia as purgatory is the purview also of Patrick White, three of whose novels, Voss (1957), Riders in the Chariot (1961) and The Vivisector (1970), Karalis has translated into Greek. Karalis’ Sydney of “nowness” with its “presumed innocence” quickly brings to mind White’s “great Australian Emptiness, in which the mind is the least of possessions… the buttocks of cars grow hourly glassier… and the march of material ugliness does not raise a quiver from the average nerves.” Just as Mary Hare in Riders in the Chariot achieves the assumption of her namesake, and Alf Dubbo, whose visions of damnation go unheeded, is exalted above the morass, so too are the nomads of Glebe Point Road accorded their celestial seat. Or rather, they resemble Hurtle Duffield of The Vivisector, who achieves an epiphany via Byzantium and conjures up “Indigod,” that evanescent hue.

The spiritual outpouring at the University of Sydney facilitates a torrent of Greek lamentation which constitutes the book’s latter section of poetry. This, if you will, is the apotheosis of osmosis, where Karalis, like Menny with his humanist Kaddish, sings praises, exaltations and psalms to and for the deceased.

Like the Epitaphios, this poetry can channel their voices: “‘Behold, Road,’ they say, ‘we are the sunken icons, / The unloved, who never returned home or / even looked homewards, angels and devils.’” (‘The Song of Remembrance’).

Sometimes it acts as invocation: “City of misspoken intentions, sinister politicks, wasted farewells – / oh, your lethal, remorseless rhetoric: / we must revive their myths / and conquer time anew…” (‘Ode to Sydney’).

By now, religious reverence has been restored ‘the City’ and the River Styx detoxified, as in ‘The Pilgrims’, where a deity resembling the Rainbow Serpent wends its restorative path: “It was raining yesternight when the great snake / slipped through the sky… / The gardens and the trees became green again… / The dust was washed away, the / beloved stream of the road was cleansed / old shoes, plastic, garbage and empty beer bottles.”

In ‘The Mythical Method’, Oedipus returns. In ‘Confronting the Lord’, so does Bennelong, “Silent, broken, defeated, an airy spectre, / despite his firmness and hardihood, Homeric…”

Only through a radical form of osmosis, the sharing of our common experience as nomads, can any form of nostos or homecoming be achieved.

“The individuals described are re-imaginings of actual personalities,” writes Karalis in the ‘Epilogue to Style’, and indeed The Glebe Point Road Blues recalls Allen Ginsberg’s Howl (1956) in its documentation of the lives of lost souls, culminating in ecstatic exaltation. Part Beat, part funereal Byzantine, the book fixes the forgotten of Glebe Point Road in a kind of lexicological gold leaf. One turns the pages like a deck of Greek icons; the portraits are encoded, both burnished and filigreed; their subjects proclaim and gravely genuflect.

And, most importantly, they live on forever. The Glebe Point Road Blues is a superlative achievement.

David Roberts is the author of Young Love and a regular contributor to Kalliope X.