Essay

On Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein

by GARY GRANT

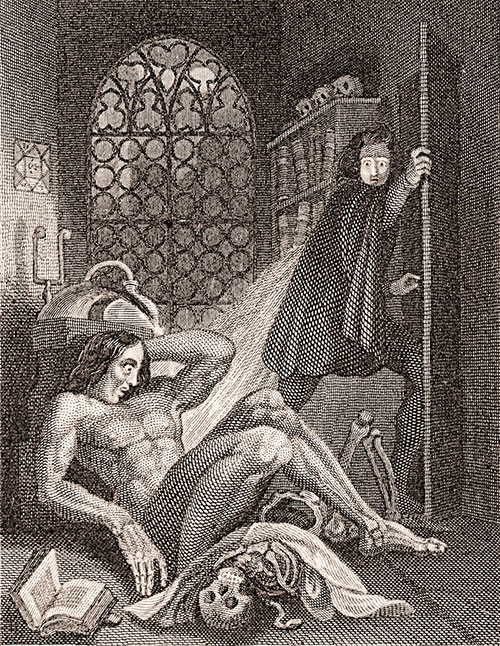

Illustration by Theodor von Holst from the frontispiece of the 1831 edition.

When nineteen-year-old Mary Shelley, nee Godwin, anonymously published her novel Frankenstein in 1818 she dedicated the book to her father, William Godwin. Although he was a brilliant, radical thinker and writer who took pains to direct his young daughter’s intellectual development, Godwin ultimately rejected his daughter’s life choices that closely mirrored his own and became estranged from her. Her mother, Mary Wollstonecraft, the groundbreaking feminist thought leader died days after the birth of her daughter. Young Mary grew up steeped in Wollstonecraft’s intellectualism, but was denied her mother’s love, care and guidance. With these fraught or non-existent connections, Shelley developed her novel Frankenstein around themes of turbulent filial relationships and parental abandonment.

Shelley was also drawn into a socially unacceptable romantic relationship with Percy Bysshe Shelley, a famous older man who was already married. While Mary Godwin and Percy Shelley eventually married after his wife’s suicide, their scandalous liaison not only severed the parental cord with her father but drew her into a circle of intellectuals who were tenuously bound by the social mores of early nineteenth century Britain. They were, however, keenly aware of the swiftly shifting social and political currents of the day. These connections and influences also found their way into Shelley’s characters and the plot of Frankenstein.

In spite or because of these life experiences, Shelley succeeds in constructing a complex, multi-layered gothic tale that continues to thrill the casual reader and challenge the most astute academic.

Shelley’s story of the tragic ambitions of Victor Frankenstein, the brilliant but narcissistic and undoubtedly mad scientist, could easily have begun as she originally planned with the opening line. ‘It was on a dreary night of November, that I beheld the accomplishment of my toils’ (Vol. I, Chap. IV). Instead, Shelley cleverly chooses to frame her main plot within a bracket story and lets the intrepid Captain William Walton open and close the book in letters to his beloved sister, Margaret. The reader never meets Margaret who hovers like a ghost over the action of the novel and not coincidentally shares the same initials as Shelley’s mother, Mary Wollstonecraft.

Shelley’s bracket story serves to introduce and reinforce the themes and personalities of the novel’s plot lines. Further, in another show of originality, Shelley inserts a confessional and amplifying text, narrated by Frankenstein’s monster into the middle of the novel. It is a testament to Shelley’s skill that rather than confuse the reader, her box within a box within a box plot device clarifies and enriches the story.

Like Frankenstein, Captain Walton is on an ego-fueled and ultimately unsuccessful quest for fame. Walton’s obsession is to sail to the North Pole or find the fabled Northwest Passage where he, ‘shall satiate my ardent curiosity with the sight of a part of the world never before visited, and may tread a land never before imprinted by the foot of a man’ (Vol I, Letter 1). His ambitions mirror Frankenstein’s even more grandiose and fantastical goal to ‘discover the cause of generation and life; nay, more … bestow animation upon lifeless matter’ (Vol. I, Chap. III).

These audacious characters quickly come to symbolise not only the male dominance of the period, but two of the major social trends sweeping Britain in the early years of the nineteenth century: Walton searches for fame and adventure in exploration, and Frankenstein chases the growing power of science and innovation. Both men are obsessively driven by the seemingly incompatible goals of discovery and the projection of the new, while holding on to the desire to recreate a prelapsarian world. Walton wants to walk in a literal Garden of Eden of ice and snow, and Frankenstein wants to blasphemously imitate God’s miracle of animating life.

The two men also share cultural and class similarities and possibly homoerotic predilections that Shelley could only hint at, given the social mores of the early 1800s. Both men are about the same age (late twenties) and are loners who long for the human companionship (primarily male, secondarily female) their ambitions and societal norms deny them. Both have the financial wherewithal to indulge their vanity-driven dreams. Walton sums up his advantages in one of his letters to Margaret like this. ‘My life might have been passed in ease and luxury; but I prefer glory to every enticement that wealth places in my path’ (Vol. I, Letter 1). That line could easily be a quote from one of Frankenstein’s mysteriously infrequent and unquoted letters to his beloved father, bosom friend Henry Clerval, or his loved but neglected first cousin/fiancée, Elizabeth.

Walton and Frankenstein are brought together by fate (and Shelley’s pen) in the harshest of environments on a seemingly doomed ship locked in ice, not unlike both men’s ambitions that are locked in their own narcissism. Walton quickly comes to feel that he has found his soulmate in Frankenstein. He confesses to Margaret that, ‘I began to love him [Frankenstein] as a brother; and his constant and deep grief fills me with sympathy and compassion. He must have been a noble creature in his better days, being even now a wreck so attractive and amiable… I have found a man who, before his spirit has broken, I should have been happy to have possessed as the brother of my heart’ (Vol. I, Letter 4).

Sensing and possibly reciprocating Walton’s deep connection and recognising his impending mortality, Frankenstein shares his life story with his new friend, and thereby creates what amounts to a book-length Freudian talk therapy session, with Walton as the analyst, Frankenstein as the analysand, and Margaret as the silent supervising analyst.

Frankenstein recounts his idealised childhood of perfect happiness with a loving father and mother, siblings, dear cousin who it is planned will be his wife, and the life-long and well-loved friend, Clerval. Nothing is denied him. Everything is encouraged. Home, social position, monetary resources, and academic opportunities seem to bring all things within Frankenstein’s grasp. However, the promise of his youth and heteronormative life is derailed by his fatal flaw of obsessive ambition. The fruit of this hubris, the Creature who he literally pieces together and then mysteriously animates with life, turns his brilliant promise into a horrific fall. The advantages and happiness of his childhood make the barren ‘childhood’ of his creature even more starkly tragic in comparison.

Shelley’s subtitle, The Modern Prometheus, was not chosen carelessly. Like Prometheus who died bringing the fire of knowledge to mankind, and Adam and Eve who were banished from the Garden for eating from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, Frankenstein pays dearly for his attempt to play God.

Frankenstein’s horror and remorse in his creation results in his rejection and abandonment of the ‘child’ he has created. Unlike the nourishment and encouragement Frankenstein received as a child, he abandons his own progeny in an infantile state, without nurture, guidance, sustenance or even language. The pain of this rejection and the Creature’s subsequent development is eventually shared with Frankenstein in detail in the innermost ‘box’ of the novel. The Creature’s inability to cope and his all-consuming anger at being set adrift in the world becomes yet another extended talk therapy session in which Frankenstein is the analyst and the Creature is the analysand (Vol. II).

We can only assume that in this case Frankenstein is as careful and true a reporter of what he is being told as Walton is of Frankenstein’s own tale. The Creature is obviously the hero of his own story and his retelling is possibly warped by his hurt and anger, but he tells his tale and conveys his point of view.

By the end of the ‘therapy session’ in Volume III Walton’s ship is breaking free of the ice (a literal break through). Frankenstein’s talking cure session succeeds in releasing both him and Walton from their inner constrictions. However, facing mutiny by his crew, Walton has agreed to give up his ambitions and sail south to the safety of home. This may also be read as his reluctant acquiescence to return to a heteronormative life without his soulmate, Frankenstein, who continues to declare his intention to follow and destroy the Creature he created.

Frankenstein too is ultimately forced by his deteriorating health to abandon his effort to rid the world of his creation. Ever the tenacious controller, Frankenstein tries to persuade Walton to take up the mantel of his obsession to rid the world of the Creature after his death. Fortunately, the talking cure has worked to the extent that Walton recognises Frankenstein’s obsessive quest for what it is and refuses, thereby saving himself from joining those who have already perished on the altar of the madman’s hubris.

Interestingly enough, the Creature himself is the one who lives on to carry out his creator’s final ambition. Frankenstein and this ‘monster’ are each other’s obsessions and reasons for living at the end of the novel. When Frankenstein dies, the Creature (who miraculously is ever-watchful of his creator’s actions and whereabouts) realises he must end his own life as well. The mutual drama of obsessive revenge has played itself out.

In speaking of the now dead Frankenstein, the Creature points to the lifeless body and says, ‘That is also my victim! In his murder my crimes are consummated; the miserable series of my being is wound to its close! Oh, Frankenstein, generous and self-devoted being, what does it avail that I now ask thee to pardon me. I who irretrievably destroyed thee by destroying all thou lovedst’ (Vol. III, Chap. VII). In the end and in the most perverse way, Frankenstein loves his creation, and the self-loathing creature loves his creator.

Like most great works of literature, Shelley leaves the final interpretation of her story in the readers’ hands. What fascinates people about the character of Victor Frankenstein and his Creature, so many years after their introduction to the public? The answers are as individualised as the readers themselves.

For those inclined to analyse through a feminist lens, Frankenstein’s usurpation of woman’s role in the production of life is the central horror of the novel. His successful creation of life effectively abrogates woman and violates the basic tenants of the miracle of birth. Women are pushed into irrelevance and made virtually invisible. As a result, a monster is created that wrecks his maker’s life and the lives of all associated with him.

Another option is a Freudian reading. The story’s frightening essence is the playing out of the Oedipus complex with tragic results. The Creature (the ‘son’) and Frankenstein (the ‘father’) fail to negotiate the separation phase, and the creature literally leaves his creator/father’s life in ruins.

Frankenstein’s abandonment of the Creature after his ‘birth’ results in the Creature’s inability to successfully move from the id through the ego to the super-ego phases. Frankenstein’s unsuccessful attempt to rectify his hubristic error by killing the Creature fails because the forces unleashed by his experiment are too powerful to be controlled or reversed, or the taboo of filicide is too strong. The Creature, in turn, realises that he cannot move past the id and ego phases without the love, support and guidance of his creator, and is doomed to a barren life without the ability to mitigate his baser instincts by developing super-ego. Faced with this knowledge, the Creature resolves to end his own life and thereby satisfy the ambition of his ‘father,’ Frankenstein.

Both interpretations, as well as many others, have validity.

In my reading, however, the shock of Shelley’s story is that we can grow to love our obsessions and the darkest sides of our personality born of ambition, weakness and moral turpitude. Further, the ultimate horror we face is ourselves. In spite of our good intentions, we are truly products of the fall in the Garden, and at some deep level know that we concurrently contain the capacity for the ultimate good and the ultimate evil coexisting in fluctuating dominance. We can love our highest objectives while holding tightly to our darkest obsessions. We are able to rationalise this push and pull of our best and worst instincts yet can never forgive ourselves for being able to do so. The resolution of this conundrum ultimately lies with each reader and the life experiences they bring to Shelley’s dark story of hubris and obsession.

Gary Grant received a degree with honours in history, economics and political science from Denison University and a Masters’ degree in international relations from the Walsh School of Foreign Services at Georgetown University in Washington DC. He continues to pursue his life-long interest in comparative cultures and religions from his home in St Louis, Missouri, USA.