Review

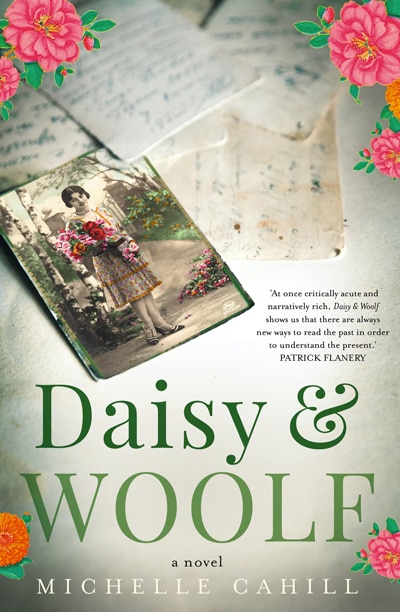

Daisy & Woolf

Michelle Cahill

Review by HARIKLIA HERISTANIDIS

Hachette, $32.99 pb. 296 pp.

‘I did not know the dead could speak until today, when I received a letter from my mother.’ So begins Michelle Cahill’s first novel, Daisy & Woolf, an ambitious work that embraces many themes: motherhood and daughterhood, grief and guilt, sexuality and power, connection, space and time, class and colonialism.

The eponymous Woolf is novelist and essayist Virginia Woolf, while Daisy is a minor character in Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway. A modern classic of English literature, published in 1925, the novel has been assiduously studied and written about for almost a century. It has also inspired, or been a springboard, for many plays, films and novels. The most well-known being The Hours by Michael Cunningham, which was Woolf’s working title for Mrs Dalloway. Daisy & Woolf is Cahill’s offering.

Structured as a story within a story, the protagonist of Daisy & Woolf is Mina, an Australian writer of Anglo-Indian heritage —much like the author herself— who is writing a novel about Daisy Simmons, also Anglo-Indian.

Mina’s story, which begins and ends the book, is told in first person. Daisy’s story—scattered throughout Mina’s narrative—is part diary entries and part epistolary. Some of the letters are written by Daisy, while others are addressed to her. There are also (fictional) letters by real-life figures such as Virginia Woolf’s sister Vanessa Bell and the suffragette Sylvia Pankhurst, and by other characters from the pages of Mrs Dalloway.

Although Mina claims that, ‘She [Daisy] isn’t anything like me,’ pulling Daisy out of Clarissa Dalloway’s shadow is, ‘a story that is mine to tell and not Virginia Woolf’s.’

It has become increasingly unacceptable for white authors to write stories about people of colour. Particularly in the first person. Mina does not like the way Daisy is sidelined in Mrs Dalloway. But clearly not every character can be a protagonist, and white, middle-class women like Virginia Woolf, by and large, write novels featuring white, middle (or upper-middle) class characters like Clarissa Dalloway.

Mina identifies with Daisy. Both are Eurasian and both are marginalised. Daisy by Virginia Woolf, Mina by the literary scene in Australia. The latter bemoans the ‘reductive reviews’ of her work, and the ‘gatekeeping’ that prevents her work being published in newspapers, even after she wins an international literary prize.

The novel begins with Mina in London, where she is teaching a university class in narrative poetry, while conducting research on her book about Daisy. She grapples with finding a voice for the character, whilst coming to terms with the death of her mother. Mina recounts travelling to the South Coast of NSW for her mother’s funeral. Later, back in the UK, she goes by train to Lewes in Sussex. Woolf lived nearby for a time with her husband Leonard. Mina also visits Rodmell, where Woolf’s cremated remains are buried. Later still Mina flies to Kolkata for research, to New York to participate in a reading and to China for further tangential research on Julian Bell, Virginia’s nephew, and his Chinese lover Shuhua, a writer and calligrapher. Along the way Mina runs into old and new loves of both sexes and thinks about her teenage son Sam, left in Sydney with his father.

Like Mina, Daisy too has left her son behind—in boarding school in Calcutta, while she travels to London by steamer in 1924. Daisy has cast off her husband and unhappy marriage to reunite with new love, Peter Walsh. The plan being to annul her marriage and marry Peter, a more prominent character in Mrs Dalloway.

Shifts in time and tense in Daisy & Woolf reflect Woolf’s similar preoccupations in Mrs Dalloway. At times it seems Cahill is trying to do too much. Locations come and go, as do peripheral characters, sometimes with little or no context. How does Luke fit into Mina’s life? or Berndt? Perhaps Cahill is making a point? Like Daisy there is more to them than a brief mention in someone’s novel. They live and breath and are the protagonist of their own lives—and yet, they are not. They are fictional characters.

Like women who reject the traditional roles, from Anna Karenina to Madame Bovary, Daisy’s end is not the happy one imagined when she leaves her army major husband and sets off for England. A man may neglect or leave his children for work or to focus on his art, with the sure knowledge that his wife or partner will support his endeavours and carry the family load. But when a woman does so, how harshly she is judged.

I confess to have fallen, eyes open, into the author’s trap. Despite being a woman and a writer, my immediate reaction towards Mina (and also Daisy) was disbelief that a mother would leave her child for an extended period. Of course Mina does not emerge unscathed either. Her guilt radiates across generations. She berates herself for neglecting her son, and cannot forgive herself for being absent as her mother died. Indeed the most powerful sections of the book centre on Mina’s grief over her mother’s death. Her loss in these sections is moving and palpable.

As a woman it is difficult to be an artist. Mina says, ‘I was naive. I wanted to believe that love and fiction are accessible destinies.’ Yet in the concluding chapter of Daisy & Woolf, Mina is at the prestigious Varuna writers retreat. Despite everything, Mina is not entirely powerless. She has her own money and a room of her own in which to write, as Woolf would say. She has the wherewithal to fly around the world to attend conferences and conduct research for her novel.

Perhaps the core theme of this profound novel, the underlying thread that pulls the other themes together, is the cost exacted on women who choose the artist’s life and/or selfhood, over the bonds of motherhood. As Mina says, ‘The artist, the writer, is always an outsider.’

Hariklia Heristanidis is a Melbourne writer. Her novella and short story collection, All Windows Open (Clouds of Magellan Press) was shortlisted for the 2013 NSW Premier’s Literary Awards. She is currently working on a new novel.