Fiction

Songs for the Dead and the Living

An excerpt from a novel in progress

by SARA M. SALEH

On the first day of school, the September sun was nowhere to be seen. Jamilah was up and ready in last year’s uniform an hour before the school bus was due. She wore her white shirt, which stretched over her uninvited, inflating chest, and a navy-blue skirt, her thick hair bursting to come out of the matching navy scrunchie.

It was just Jamilah and her cousin Lobna, since Amal had traded high school for married life a few weeks ago. Amal was probably relieved since she hated going to school. If Mama had it her way, they would both quit school and get married like her older sisters, or helping at home where she could keep an eye on them.

‘Things are different for this generation, Amira. They can choose to make something different out of themselves,’ Baba said.

‘What’s wrong with being a homemaker, a mother? That’s what we all are and they should get used to it,’ Mama said, ending the conversation as though she was zipping closed a suitcase.

Jamilah did not know what to make of herself yet – but she knew it was not homemaking or mothering. She appreciated solving mathematical problems using step-by-step formulas, though Lobna said they were an ancient language impossible to decipher. But numbers nestled in parentheses, cosines and sines and tangents, made sense to Jamilah, unlike the events she learned about in history class; the men who started world wars and still she couldn’t tell who’d won.

Lobna and Jamilah grabbed their laffehs and made their way downstairs, slugging their oversized bags like dead carcasses over their shoulders. The smell of jasmine bushes balmed the driveway. They ate quietly, the Lebanese flatbread dripping with zaatar doused in olive oil, as they waited inside on the building entrance steps. ‘Zaatar makes you smart’, Mama proclaimed every single time as she deftly rolled the laffeh.

Beep, beep, beeeeeeeeeep the small red and white bus honked as it pulled up.

‘All right,’ Lobna barked at Usta Ammar. ‘Don’t wake up Beit Samra.’

•

Eastwood College was in the neighbouring town of Bshamoun, a 15-minute drive down Beit Samra’s winding road, the main way in and main way out. It was an English curriculum school established almost a decade earlier, by a Lebanese-American educator, Amin Khoury and his ajnabi wife Carol Hawking. Headmistress Hawking was a tall white woman who aggressively pronounced her ‘rs’ like a motor left running, and dressed like she herself was a pupil. Two-piece dark grey suit, the shirt tucked into the skirt.

Neither of them was interested in replicating the French missionary schools, which had initially been established to counter the spirit of the Arab movement. Though the schools promised education, students were not allowed to speak their mother tongue. French was promoted to foster loyalty to an identity more ‘French’ than ‘Arab’. One couldn’t turn on their master if their master taught them how to speak, and decided when they could speak.

But Amin and Carol were only interested in smart business decisions, and given the power of the US, which had flexed its political and military might during the Cold War, they both believed English was the future. At first, they wanted to attract children of rich diplomats who opted for English-speaking suburban schools away from the city fighting. What they also got was an undocumented Palestinian like Jamilah, who only had a flimsy identification document known as a waseeqa. Eastwood discreetly took her in, so long as they paid the fees on time, no questions were asked.

Jamilah understood she was lucky, Mama had reminded her of this whenever she brushed the tangles out of her hair, or tested Jamilah’s Arabic vocabulary, or sat with her as Jamilah practiced conjugation.

‘Eastwood is burning a hole in your baba’s pocket,’ Mama said as the comb tugged onto Jamilah’s damp tangles. ‘It’s a blessing you have access to this school, most Palestinian kids don’t.’

Many of the undocumented Palestinian kids Mama was referring to couldn’t afford schooling and ended up in underfunded, under-resourced schools run by the United Nations in refugee camps, official and unofficial, that had sprouted across Lebanon over the last few decades.

Even though they were Beit Samra locals, Jamilah was certain her teachers could tell she was an imposter, every bit a Palestinian, just by looking at her, the secret strapped around her skin, sitting in the pouches of her sleeves.

‘Those Palestinians are bottom feeders, Samer,’ a student in their class proclaimed one lunchtime recess, a cookie in his round hand, crumbs crusting his chin.

‘They’re bottom feeders,’ he repeated in a billowy voice that had yet to fully break. ‘My dad says those stone-throwers have ruined the country so send them back – they’re not our problem!’

Jamilah, who was in conversation with Lobna at the time, stopped mid-sentence, her face burning beet red. The boy’s words clawed at her ears, the image of her fleeing grandmother pregnant with Baba flashed in front of her. She turned to Lobna, who stood motionless like one of the dead bugs they found on the balcony on humid summer nights. Before either of them knew it, Jamilah was running over to Joe. They were almost the same height, but her rage had expanded her as she somehow towered over him.

‘What did you say?’

‘Why do you care about those animals? Your loyalties should be with Lebanon,’ Joe cried as he stepped back, surprised at the outburst. He wasn’t used to anyone standing up to him, let alone Jamilah.

‘The war has murdered so many, including our family,’ Jamilah cried, her mouth spasming. Before she could react any further, Jad quickly stepped between them with the authority of an older student. ‘Whoa whoa, khalas, enough.’ His Russian accent always weighed heavy on his Arabic tongue when he was nervous or stressed. ‘He’s sorry… Right, you’re sorry?’

Joe paused, deciding it was better for his dignity to leave it than to admit to Headmistress Hawking that a girl intimidated him, especially one as scrawny as Jamilah.

For the next week, the incident followed Jamilah like a fog. She wasn’t sure what she was more upset about: the fact that people like Joe believed what they did, or by her uncharacteristic reaction. Was being born to a Lebanese mother not loyal enough in this country? Was growing up, relinquishing your youth to a country not loyal enough? Sweating underneath its sweltering sun and covering yourself in its dirt not loyal enough? Was climbing its wildflower hills and pigeon-filled rooftops, singing its songs, and befriending its kaleidoscope of children not enough? Was caring about a Lebanese boy not loyal enough? One who was ‘nos’, a halfie like she was, but whose status was respected in Lebanese society because he was born to a Lebanese father. Either way, she was grateful Jad had stepped in when he did.

The bus pulled up in front of the three-building school crouched behind a collection of triangular shaped fir trees. And there he was, Jad, her Lebanese halfie, his presence a flare in the sunless September morning. He casually leaned on one of the trees, arms folded over his buttoned-down white shirt. His shaggy brown hair swept to the side.

‘Someone’s waiting for you,’ Lobna teased her cousin and waved at Jad from a distance.

‘Ahlan! You’re here early, neighbour. Anyway, don’t stay out here too late,’ Lobna said to them, smirking as they stepped off the bus.

‘Bye, Lobna,’ Jad smiled, wrinkling the brown mole on his left cheek.

Jamilah and Jad lived two streets away from each other. By the time Jad’s family had moved from Russia when he was nine, Jad could string along complete sentences in Arabic. His father left Lebanon to study mechanical engineering at Tomsk State University. During his final year as a teacher’s assistant, he met Jad’s mother, a first-year biomedical student at the time. They got married a few years later and lived in Russia until Jad’s grandfather was diagnosed with lung cancer, so the family moved.

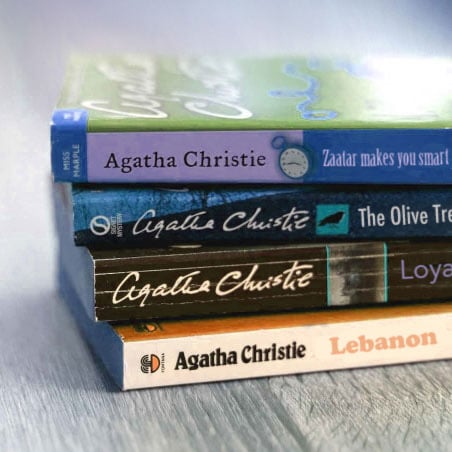

Jad, his younger sisters Janet and Maya, Jamilah, and Lobna, spent countless afternoons playing soccer with the rest of the neighbourhood kids in Beit Samra. Its street corners and alleyways and stubby green patches cradled them on scorching summer days and wet winter weekends. They’d find themselves on the rooftop of Jad’s building held captive by rambunctious card games with Janet and Maya. And when the girls had finally tired, Jad and Jamilah would spend hours on the rooftop’s swing chair, their legs dangling from underneath the apricot-coloured umbrella as they read murder novels by a Western author named Agatha Christie. They were yellowing copies gifted to Jad by his uncle who lived in the US. Comfortably wrapped in a dusk breeze, their reading sessions were followed by long, intense conversations about the identity of the killer and which one of Jamilah’s sisters was most likely to be the best killer. ‘Definitely Layla,’ Jamilah and Jad said simultaneously and burst out laughing, knowing that Layla, beloved by all, was considered the sweetest and most polite of the Husseini girls.

Jamilah did not know exactly when her feelings grew for Jad, or if they were simply there all along. Although she had yet to confide in her cousin, she knew Lobna was smart enough to guess that Jamilah was not alone during her recent secret summertime adventures in Beit Samra’s hidden pockets. Playing street soccer with the rest of the neighbourhood was a cover story that still worked with Jamilah’s parents, not with Lobna. Jamilah’s mind wandered to her summertime exploits.

‘Hi.’ Jad’s voice brought her back to the present. He cocked his lanky neck, long arms in uniform pant pockets.

‘Hi.’ Jamilah looked away, as though directing her greeting to the tree trunk behind him. This was the first time they had spoken since their adventure on the last day of summer the week before. The adventure where that thing happened.

‘How are you?’ he asked shyly, standing at a distance.

‘Fine,’ she shrugged casually, her spine tingling as she remembered their last conversation. They stood, two apostrophes awkwardly circling into each other.

His voice sliced the silence. ‘I got you something. A gift.’

Jamilah looked up, thrown off balance. ‘Really?’

He put his hand in his back pocket and took out a maroon sleeve encasing a sleek, gunmetal camera the width of his palm. Jamilah gasped at the sight of it glimmering.

‘I asked my uncle in the US to send it. It’s supposed to be the best. All artists need a little inspiration from time to time, and where to find it but in nature.’

Jamilah remained speechless as she inspected the camera carefully, as though it would detonate at her touch. ‘I can’t accept this.’

Jad laughed, his teeth shiny like little pearls, his mole crinkling. ‘You can, you can take photos of all the trees you’re obsessed with – and then draw them. The possibilities are endless. Cedar trees and citrus trees and apple trees and fig and date and … olive trees.’

Every person who had Palestine in their blood understood the significance of remaining steadfast, of standing tall, like the olive trees. Dark and narrow, olive trees were not just food and financial means to sustain whole families. They brought people together every year during harvest, each harvest a journey of a hundred shared stories between Palestinian families and neighbours as they picked and washed and sorted and pressed olives.

Jad planted the camera in Jamilah’s hand. She was taken aback by Jad’s gift, knowing that between this school and Maya’s special needs school, his working-class parents were being siphoned of money. Before she could make up her mind about whether she was going keep it or not, the bell rang.

‘Come on, Jamilah!’ He gestured, dashing ahead.

She held the camera tight and ran behind him as the autumn scraped at their boots, its burnt orange and red leaves everywhere.

Sara M. Saleh is a human rights activist, writer, poet, and the daughter of migrants from Palestine, Egypt and Lebanon, currently living on Gadigal land. Her award-winning poetry and fiction has been published in national and international anthologies. Her debut novel Songs for the Dead and the Living will be published by Affirm Press in 2023