Memoir

Helpless

by AMRA PAJALIC

Every Thursday after work I drove to my mother’s house and took her shopping. She was a bipolar sufferer and had stopped driving ten years earlier. My stepfather Izet was her primary carer, but he hadn’t been feeling well so I changed our regular weekly visits to outings.

At the shopping centre, I walked with my mother to her favourite clothes shop and then to the food court where she sat, the arthritis in her hips and legs limiting mobility, while I ordered a coffee for her and hot chocolate for me. We talked about our week and Mum brought me up to speed with gossip in the Bosnian community.

On this day our conversation was different.

‘I have something to tell you.’ My mother blinked. A tear seeped from her eye, smudging her mascara. She always took pains with her appearance on these outings, her make up immaculate with black eyeliner highlighting her green eyes, her light brown hair styled, her jewellery coordinated to match her clothes.‘Izet told me he was sexually abused as a child, by his older brother.’

My stepfather was 63 and had been married to my mother for 31 years when he confided in her. She was the first person with whom he had shared his secret. In Masculine Norms, Disclosure, and Childhood Adversities Predict Long-term Mental Distress among Men with Histories of Child Sexual Abuse, researcher Scott Easton labels this phenomenon of keeping a secret into adulthood as self-silencing. A result of the shame, stigma and self-blame.

Izet didn’t remember how old he was when the abuse began and ended. My mother asked a few questions, but she didn’t wish to stir up his trauma further. Easton mentions studies that found sexual abuse of males usually began at eight or nine years of age, and ended when the victim was strong enough to fight off the attacker. This mirrored my stepfather’s case.

‘Did he ever tell his parents?’ I asked.

‘You know what they were like.’

Izet’s mother suffered from depression and never left the house. His father was breadwinner and caregiver. He worked a lowly job as a porter at a hotel in Bosanska Gradiška. The family was dirt-poor. Izet and his four siblings were raised in a one bedroom shack with earthen floors and ramshackle walls.

‘Do you think his brother abused the other siblings?’ I asked.

‘He didn’t say.’

Izet’s siblings had emigrated to other European countries. Only my stepfather and his brother remained at home, a common occurrence in Bosnia due to economic hardship. Izet was 32 when he married my mother and emigrated to Australia.

I imagined my stepfather spending most of his adult life sharing a house with his abuser, the two of them sleeping under the same roof, and shuddered with revulsion.

Izet married my mother when I was 10. My mother was advised not to have any more children due to her bipolar condition. When she told my stepfather, he said he did not want his own biological children. He told her my brother and I were his children, and that was how he treated us.

While I called him by his first name and noted his relationship as my stepfather, out of respect to my biological father who passed away when I was four, to all intents and purposes Izet was the father who raised me. Growing up, he ferried me wherever I needed to go. When I was 13 and was beaten up while buying bread at the milk bar he was the one who tracked down the girl’s home address and visited their parents, using his anger and rage to ensure they kept clear. When I went to a nightclub and didn’t want to accept a ride home from a drunk friend, Izet collected me. He was always there, devoted and utterly loving.

My mother was completely dependent on my stepfather and he was attentive to her. He completed all household chores—grocery shopping, paying bills, doing the clothes washing and hanging it out, and vacuuming. My mother only cooked. When she was diagnosed with agoraphobia and couldn’t leave the house, she and Izet developed an intense co-dependent relationship. Their respective mental health issues intensified as they retreated from the world and became more inward looking. Sometimes it seemed they hurt each other as much as they helped each other.

While being a carer for my mother took a heavy toll on Izet, I gain comfort knowing it also helped him. Before my mother married Izet our lives were plagued by loss and trauma. My mother struggled under the burden of being a sole parent and she was frequently hospitalised after suffering breakdowns. My stepfather provided much-needed stability.

Throughout his life Izet was obsessed with maintaining his physical strength, training with weights and taking supplements. He was 182 centimetres tall and had a robust, intimidating physique. Now I know this ensured he was never again vulnerable to abuse. He was 56 when he had a heart attack that required a quadruple bypass. Izet didn’t smoke or drink alcohol, was fit, and his cholesterol was in the healthy range. But he did suffer from depression and frequently isolated himself from people. Case studies show that male sexual abuse victims present with depression. One study found depression in 88 per cent of participants and another 100 per cent.

After his heart-attack Izet’s strength was greatly diminished and his rage grew proportionate to his physical weakness. He became overbearing and difficult to be around, his anger and bitterness coating every interaction.

Living with him was fraught. He was paranoid and fearful. He spent nights staring out the living room window. If he thought he was being somehow wronged, he threatened to beat people up. These occurrences could be as innocuous as the boy at K-Mart who couldn’t tell him where the weights section was, or the server at Dunkin’ Donut who assumed Izet was a senior citizen by asking for his card. These incidents set off what Easton calls ‘hyper-masculine persona’, which is another defence mechanism.

When my mother told me Izet’s secret, I finally understood the reasons for some of his baffling behaviour.

A 1982 Mental Health Research Institute study identified an overrepresentation of diagnosis of schizophrenia in the state of Victoria, with 40.8 per cent of Yugoslav males being diagnosed per 10,000 at risk, as opposed to 16.2 per cent of Australian-born males. This over-representation was also present with females.

When a reassessment was conducted in a sample of 50, in the patients’ native language, only 13 of the 50 patients (26 per cent) were re-diagnosed as schizophrenic. In the remaining 37 cases (74 per cent), the diagnoses ranged from affective psychosis and/or affective disorder, symptomatic psychosis, paranoia, and alcoholic hallucinosis and alcoholic paranoia. The researchers concluded that there were a number of reasons for this, most of them relating to language issues.

The one that struck me most was ‘the clinician’s unfamiliarity with the patient’s culture leading to the attribution of psychopathological behavior to culturally appropriate responses.’

The Bosnian language is full of hyperbole and allusions to violence. When we see a child sleeping peacefully we say ‘Spava ko zaklan’ which roughly translates as, ‘The child is sleeping as if its throat is cut.’ When we joke we say, ‘Da bog da crko’, which means ‘I hope you die.’ When it is a windy day we say, ‘Ubiće te vjetar’, ‘The wind will kill you.’ There is much use of ‘I’m going to kill myself’, or ‘I’m going to kill someone else.’

Izet’s language was peppered with this kind of talk. When he said as much to my mother’s psychologist, he wanted to place Izet on a mental health plan. My stepfather violently refused.

He believed the medication prescribed after his heart attack was responsible for his declining physical health and had caused body myositis, a progressive muscle disorder characterised by muscle inflammation, weakness, and atrophy that usually develops after the age of 50. He was a man possessed by self-diagnosis. In the year before he died he attended over 20 doctors at 18 different clinics. Tests included a CT of his chest, abdomen and pelvis, an ultrasound of his abdomen, an MRI of his brain, ECG monitoring of stress and doppler ultrasounds to check blood flow in his legs and arteries.

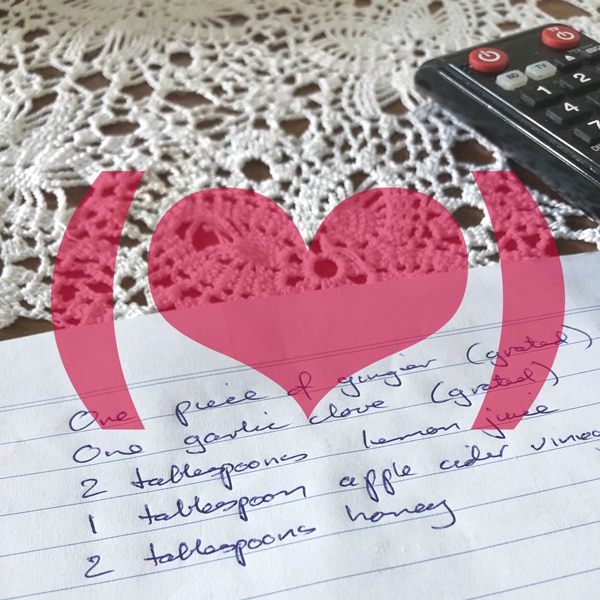

When the medical profession didn’t confirm Izet’s suspicions, he undertook his own online research. He copied out various natural remedies and supplements on scraps of paper. Notes like, ‘apple cider vinegar, two spoons per day.’ Or ‘one piece of ginger (grated), one garlic clove (grated), 2 tablespoons of lemon juice, 1 tablespoon of apple cider vinegar, 2 tablespoons of honey.’ Another read, ‘for arteries hemp seed’ and ‘white vinegar dilute 1:3 water distilled at night.’ One day he was nauseous and could barely stand without vomiting. My mother found his Vitamin C bottle nearly empty. Izet had taken nearly 20 tablets a day, based on something he read on the internet.

One night he had pains in his chest and my mother called an ambulance. The doctors found no issues with his heart. Believing that his struggle to breathe was a sign of an anxiety attack he was referred to a psychiatrist. My husband went to pick up Izet and found him waiting for the psychiatrist to clear him for release.

While they waited, Izet became agitated and ranted to other patients and nurses about the terrible hospital treatment he was receiving. Some of the nurses ignored him, others attempted to engage and pacify him. He treated both with rude disregard. Embarrassed by my stepfather’s behavior, my husband placated him by being jocular. This worked for a short while, but as the waiting time stretched on Izet began to talk about how he would commit suicide.

When the psychiatrist arrived, Izet told him that he would kill himself with a rifle he was going to buy online and named the website he had researched. The psychiatrist said that he couldn’t release him if there was the possibility he would harm himself. Izet shouted that the hospital couldn’t detain him and walked out of the room. The psychiatrist called security. My husband intervened, asking the security guards to allow him to reason with my stepfather. He managed to calm Izet, who remained in hospital for the night under 24-hour guard to ensure he wouldn’t harm himself. Before being released, the psychiatrist referred Izet to counselling and prescribed antidepressants. Izet threw the referral and the prescription in the bin.

Izet believed his malaise and physical weakness had a medical cause. Yet Easton found male sexual abuse victims experience harmful outcomes four to five decades after the fact. These findings are consistent with complex trauma theory, that suggests traumatic experiences disrupt key developmental milestones in childhood and adolescence, which lead to difficulties in later life, ‘such as feelings of despair and hopelessness, unexplained physical complaints, and anger dysregulation.’

When I dream about my stepfather I am on the phone with him, calling out his name, begging him to speak, to say goodbye. All I hear is him gasping for breath before he hangs up. When I wake up in the morning my chest feels tight, and I travel back to the house I grew up in and the bungalow behind it.

As an adolescent I used to climb onto the bungalow roof via the mulberry tree whose large branches rose above it. In summer, I’d lie on a blanket and read, or slather myself in baby oil and tan. It was where I went with girlfriends to gossip, hidden from view.

The day Izet died, I was at the hairdresser with my daughter. She was getting pink tips for her tenth birthday present, when my husband called to say my mother had arrived at our house in a taxi. Izet had driven her to the swimming pool, but he hadn’t picked her up at the agreed time. He wasn’t answering the home phone or his mobile.

My husband drove my mother to the house. Izet wasn’t there. They thought they’d check the bungalow, in case he was working out the back. As they walked there, my mother worried aloud that he had harmed himself in some way. Her words rang in my husband’s ears as he pushed in front of her and opened the bungalow door. Peering inside he saw a shape behind some wood. It was Izet. He had hanged himself from the rafter beams.

They called the police. On the dining table was a note. ‘Dear wife, thank you for the golden years. I am sorry. I wish you good health and love. I will love you forever.’ Izet had drawn three hearts under his note, one for my mother, one for my brother, and one for me.

When we received the coronial investigation report, I read that he carried a framed photograph of my brother and me on his person. I gain comfort knowing we were with him in the end.

Amra Pajalić is the award-winning author of The Good Daughter, Things Nobody Knows But Me and the short story collection The Cuckoo’s Song. www.amrapajalic.com/

This is a work of creative non-fiction. All the events are true to the best of the author’s memory. Some names and identifying features have been changed to protect the identity of certain parties. The views expressed in this memoir are solely those of the author.